The History of Matsumoto Castle

Before the Construction of Matsumoto Castle

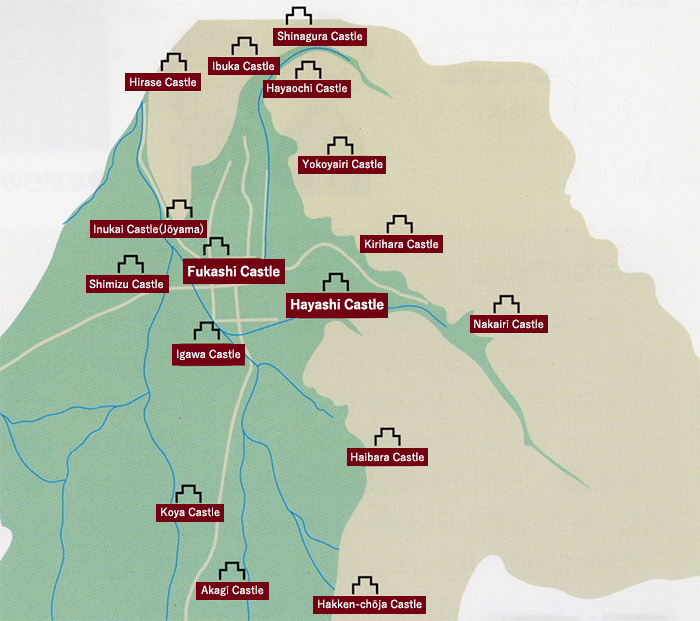

Various Mountain Castles

Even before Matsumoto Castle was built in the late sixteenth century, the surrounding mountains were dotted with castles. During the many regional conflicts of the Warring States period (1467–1600), warlords called “daimyos”built networks of wooden or stone castles to defend their territories. These are a few representative examples of the fortifications that stood in the mountains surrounding the Matsumoto basin.

Source: Watashitachi no Matsumoto-jō (Our castle, Matsumoto castle), p. 58.

- Hayashi Castle (Ōjō and Kojō) Hayashi Castle was built by the Ogasawara family, who governed Shinano Province (now Nagano Prefecture), of which Matsumoto domain was a part. Hayashi Castle stood in what is now the Yamabe District of Matsumoto. It comprised two separate structures called “Ōjō” and “Kojō” that were located on opposite ends of a horseshoe-shaped mountain ridge. In 1550, the powerful daimyo Takeda Shingen (1521–1573) attacked the area, and the Ogasawara abandoned Hayashi Castle. Portions of the stone wall that surrounded the central bailey at Kojō still remain today.

- Kirihara Castle and Yamabe (Nakairi) Castle These two castles were located deep in the mountains beyond Hayashi Castle. Kirihara Castle belonged to the Kirihara family and was positioned on a strategic mountain pass. Yamabe Castle, also called Nakairi Castle, belonged to the Yamabe family. Its 2.5-meter-high stone walls are still visible at the site today.

- Haibara Castle Haibara Castle was a large castle located in what is now the Nakayama District of Matsumoto. It is not known which warlord built this castle.

- Shinagura Castle Located in what is now the Okada District of Matsumoto, Shinagura Castle was controlled by the Gochō family.

- Kokūzōsan Castle Kokūzōsan Castle originally belonged to the Aida family and stood in what is now the Aida District of Matsumoto. Following the defeat of the Ogasawara family by the armies of Takeda Shingen in 1550, Kokūzōsan Castle occupied a frontline in the fighting between Takeda and his longtime rival, Uesugi Kenshin (1530–1578). Uesugi was based in Echigo Province (now Niigata Prefecture), to the north of Matsumoto.

- Hirase Castle Located in what is now the Shimauchi District of Matsumoto, Hirase Castle was controlled by the Hirase family. The Ogasawara family took refuge at Hirase Castle after being forced to flee Hayashi Castle in 1550. It was from Hirase Castle that the Ogasawara family planned their counterattack.

- Inukai Castle The Joyama Castle is located in Joyama, Matsumoto City, and was the residence of the Inukai Clan.In this district, fort had been existed since the Northern and Southern Courts period.This place is called the Joyama by Matsumoto citizens, popular for viewing cherry blossoms in spring.

- Igawa Castle Unlike other castles in this region, Igawa Castle was built on the plains rather than in the mountains. It was the original base of the Ogasawara family until the construction of Hayashi Castle.

Igawa Castle

- Shimizu Castle It is thought that Shimizu Castle was controlled by the Shimadachi family, who were retainers of the Ogasawara family. The castle occupied what is now the Shimadachi District of Matsumoto. Although little remains at the site today, Shimizu Castle is another example of a castle built on the plains, like Igawa Castle.

Fukashi Castle

Former Site of Wakamiya Hachiman Shrine

It is thought that prior to the construction of Matsumoto Castle, the site was occupied by a smaller fortification called Fukashi Castle. However, little is definitively known about this earlier structure or how its layout might have influenced the subsequent layout of Matsumoto Castle.

During the early Muromachi period (1336–1573), the small township of Fukashi-gō was ruled by the Sakanishi family, and it is thought they had some form of fortified manor there. It was only later, in 1504, that a retainer of the Ogasawara family named Shimadachi Sadanaga (d. 1517) built Fukashi Castle.

The Ogasawara family controlled the area around Matsumoto for many years, but in 1550 a neighboring daimyo named Takeda Shingen (1521–1573) attacked Hayashi Castle and drove Ogasawara Nagatoki (1514–1583) to the north. Shingen then established his regional headquarters at Fukashi Castle, and it is likely that he made repairs and expanded the fortifications.

Shingen’s descendants controlled Fukashi Castle until 1582, when the Takeda family was wiped out by Oda Nobunaga (1534–1582). The area then came under the control of the warlord Uesugi Kenshin (1530–1578), who placed Fukashi Castle in the hands of one of his retainers. Ogasawara Nagatoki’s son Ogasawara Sadayoshi (1546–1595) later took back control of Fukashi Castle, and to mark the return of the Ogasawara family to the area, he gave the region a new name: “Matsumoto.”

Despite their victory, the Ogasawara family did not remain in Matsumoto for long. In 1590, only eight years after their long-awaited return, they were relocated to eastern Japan. This relocation was ordered by Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537–1598), the most powerful daimyo at the time, who granted control of Matsumoto to his ally Ishikawa Kazumasa (d. 1592).

The Construction of Matsumoto Castle

The Arrival of the Ishikawa Family

shikawa Kazumasa (d.1592) was a longtime retainer of Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616), the eventual founder of the Tokugawa shogunate. Kazumasa was even entrusted with guarding Okazaki Castle, where Ieyasu had been born. However, in 1585, Kazumasa suddenly deserted and allied himself with Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537–1598). In reward, he was granted control of Izumi Province (now southern Osaka Prefecture). When Hideyoshi removed the Ogasawara family from Matsumoto Castle in 1590, he chose the Ishikawa family to replace them.

Building the Castle Keep

Kazumasa and his eldest son, Ishikawa Yasunaga (1554–1642), improved the castle grounds and began work on Matsumoto Castle. Kazumasa died only three years after his arrival in Matsumoto, but Yasunaga oversaw the completion of the Great Keep, the Northwest Tower, and the Roofed Passage.

The initial stages of construction are described in an eighteenth-century text on the history and geography of the region called Shinpu tōki (Compiled Chronicles of Matsumoto):

“Kazumasa built [the Kosanji Goten] in the second bailey and started planning the layout of the castle. Yasunaga continued his father’s work: he erected the keep, dug the outermost moat, increased the height of the earthen embankments, then laid the stone foundation for the castle, built the Roofed Passage, Kuromon Gate, and Taikomon Gate, repaired the walls, and built a tower above the gate to the third bailey. He built most of the plaster walls around the outermost moat and repaired the residences within the castle compound. He also built residences for his samurai retainers.”

Matsumoto Castle during the Edo Period (1603–1867)

Lords of the Castle

During the Edo period, Matsumoto Castle was governed by 23 successive lords from six families. The castle was the administrative center of Matsumoto domain, which roughly corresponds to what is now the Chūshin region of Nagano Prefecture. At this time, the country was divided into hundreds of such domains, and daimyos were appointed to govern them by order of the Tokugawa shogunate. Daimyos who were loyal to the shogunate would often be relocated to more prestigious domains or given an increased stipend, which was measured in units of rice called koku. Matsumoto’s strategic location and subsequently large stipend made it desirable, and the daimyos that governed the domain were often closely related to the shogun or his family.

Family Name Given Name Period of Rule Ishikawa Kazumasa 1590-1592 Yasunaga 1592-1613 Ogasawara Hidemasa 1613-1615 Tadazane

(Tadamasa)1615-1617 Toda Yasunaga 1617-1632 Yasunao 1633-1633 Matsudaira Naomasa 1633-1638 Hotta Masamori 1638-1642 Mizuno Tadakiyo 1642-1647 Tadamoto 1647-1668 Tadanao 1668-1713 Tadachika 1713-1718 Tadamoto 1718-1723 Tadatsune 1723-1725 Period of Direct Control by Tokugawa Shogunate Toda Mitsuchika 1726-1732 Mitsuo 1732-1756 Mitsuyasu 1756-1759 Mitsumasa 1759-1774 Mitsuyoshi 1774-1786 Mitsuyuki 1786-1800 Mitsutsura 1800-1837 Mitsutsune 1837-1845 Mitsuhisa 1845-1869 Family High-Level

Government PositionsStipend

(kokudaka)

1koku≈ 180LPrevious Post Next Post Ishikawa Hōki no kami (“Lord of Hōki Province”): Kazumasa

Genba no kami (“Chief of Temples and Foreign Affairs”): Yasunaga80,000 koku Izumi Province Stripped of rank,land seized Ogasawara Shinano no kami (“Lord of Shinano Province”): Hidemasa

Ukon no taifu (“Fifth-Rank Magistrate of the Right”): Tadazane80,000 koku Shinano Province,Iida domain Harima Province,Akashi domain (10,000 koku) Toda Tanba no kami (“Lord of Tanba Province”): Yasunaga

Sado no kami (“Lord of Sado Province”): Yasunao70,000 koku Kōzuke Province, Takasaki domain Harima Province, Akashi domain (70,000 koku) Matsudaira Dewa no kami (“Lord of Dewa Province”): Naomasa 70,000 koku Echizen Province,Ōno domain Izumo Province, Matsue domain (186,000 koku) Hotta Kaga no kami (“Lord of Kaga Province”): Masamori 100,000 koku Musashi Province, Kawagoe domain Shimōsa Province, Sakura domain (110,000 koku) Mizuno Hayato no shō (“Commander of the Hayato”): Tadakiyo and others

Dewa no kami (“Lord of Dewa Province”):Tadamoto and others

Hyūga no kami (“Lord of Hyūga Province”): Tadamoto (r. 1718–1723)70,000 koku Mikawa Province, Yoshida domain Land confiscated Toda Tanba no kami (“Lord of Tanba Province”) 60,000 koku Shima Province, Toba domain Abolition of the domain system (haihan-chiken) Major Events

This timeline describes some of the key events in the history of Matsumoto Castle and the surrounding domain.

Year Event Ruling Family 1504 Shimadachi Sadanaga constructs Fukashi Castle

(according to available records).1550 Takeda Shingen attacks Fukashi Castle, forcing Ogasawara Nagatoki to flee. Shingen begins renovations of Fukashi Castle. 1582 Oda Nobunaga defeats Takeda Katsuyori, functionally eradicating the Takeda family. After a brief clash between daimyos, Fukashi Castle is claimed by Ogasawara Sadayoshi, who renames the site “Matsumoto Castle.” 1590 The Ogasawara family is transferred to eastern Japan. Toyotomi Hideyoshi awards Matsumoto Castle to Ishikawa Kazumasa. Ishikawa 1593 Construction of the Great Keep, the Northwest Tower, and the Roofed Passage progresses. 1600 The Ishikawa family allies with Tokugawa Ieyasu at the Battle of Sekigahara. 1613 Ishikawa Yasunaga is implicated in a tax scandal (the Ōkubo Nagayasu Jiken) and stripped of his rank by Ieyasu.

Ogasawara Hidemasa is granted control of Matsumoto Castle.Ogasawara 1614 The Ogasawara family fights alongside Tokugawa forces during the winter campaign of the Siege of Osaka. 1615 Ogasawara Hidemasa and his eldest son, Ogasawara Tadanaga, die during the summer campaign of the Siege of Osaka. 1617 Toda Yasunaga is granted control of Matsumoto Castle. He builds more residential areas for samurai to the north of the castle. Toda 1633 Matsudaira Naomasa is granted control of Matsumoto Castle. He builds the Southeast Wing and the Moon-Viewing Tower and repairs other parts of the castle. Matudaira 1649 Mizuno Tadamoto conducts a comprehensive land survey of Matsumoto Domain. Mizuno 1686 Peasants in the north protest the high annual taxes levied on them by the domanial government. The protest leaders are captured and crucified. 1725 The Mizuno family is removed from power after Mizuno Tadatsune attacks someone with his sword on the grounds of Edo Castle. In their absence, development of the castle town is completed. 1726 Matsumoto Castle is briefly placed under the direct control of the Tokugawa shogunate, after which the Toda family is once again granted control of the castle. Toda 1727 The Honmaru Goten burns down. Its functions are transferred to the Ninomaru Goten and the Kosanji Goten. 1743 The shogunate grants the Toda family additional territory valued at 50,000 koku. 1760 Shinano Province (of which Matsumoto is part) becomes embroiled in a legal dispute regarding sanctions on shipping by horseback along public roads. 1775 A large fire breaks out in Matsumoto, and parts of the second and third bailey are damaged. 1793 The domain school Sōkyōkan is opened. 1803 Another fire breaks out in Matsumoto, and large sections of the city burn. Several samurai residences and temples are damaged or destroyed. 1816 An irrigation canal called “Jikkasegi” is built in Azumino, a village to the north of Matsumoto Castle. 1825 Protests erupt in northern Matsumoto domain as tens of thousands of peasants rise up against a sharp increase in the price of rice. 1832 The Saigawa Canal is expanded to pass through Matsumoto. 1854 A powerful earthquake damages many buildings at the castle and in the town. 1862 A samurai from Matsumoto murders two British soldiers in Edo. 1863 Matsumoto domain is ordered to help guard Uraga Bay 1864 Matsumoto domain is ordered to participate in the First Chōshū Expedition. Forces from Matsumoto are defeated by masterless samurai (ronin) from Mito domain at the Wada Pass. 1865 Fire breaks out in Matsumoto, damaging residential areas in the south. Matsumoto domain is ordered to participate in the Second Chōshū Expedition and dispatches troops to Hiroshima. 1866 A protest erupts in the south of Matsumoto domain as peasants rally against rising rice prices. 1868 Matsumoto domain allies with the new imperial government and participates in the Battle of Hokuetsu in Hokkaido. 1869 Toda Mitsuhisa, the last daimyo of Matsumoto, surrenders his territory to the emperor. 1870 An anti-Buddhist movement begins after an imperial edict separates the previously syncretic religions of Buddhism and Shinto. 1871 The shogunal domain system is abolished, and Matsumoto domain becomes Matsumoto Prefecture.

Several castle gates are demolished, and the castle is placed under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of War.

Matsumoto Prefecture is soon renamed Chikuma Prefecture, and a prefectural office is established in the castle’s second bailey.

Changes in the Meiji Era (1868–1912)

The End of Matsumoto Domain

Toda Mitsuhisa, the Last Daimyo of Matsumoto

In 1868, daimyos across Japan are faced with the choice of aligning with one of two factions: the imperial government under Emperor Meiji (1852–1912) in Kyoto, or the Tokugawa shogunate (1603–1867) in Edo (now Tokyo). Imperial loyalists had already begun the march to Edo to overthrow the shogunate, and officials in Matsumoto domain found themselves in a predicament: imperial troops would soon be passing along a major road south of Matsumoto. Should the domain remain loyal to the shogunate, or should they join forces with the loyalists? After much debate, Matsumoto allied with the emperor and quickly implemented numerous military reforms.

The last daimyo of Matsumoto, Toda Mitsuhisa (1828–1892), proactively joined a movement to “return the lands and people to the emperor” (hanseki hōkan). Mitsuhisa surrendered his territory and position as daimyo in 1869 and was appointed governor of Matsumoto domain. Around the same time, an imperial edict separated the previously syncretic religions of Shinto and Buddhism, launching a movement for the eradication of Buddhism. Mitsuhisa was particularly aggressive in the suppression of Buddhism in Matsumoto: he abolished his own family temple, Zenkyūin Temple, and ordered that all his retainers should hold only Shinto-style funerals. As a result of this movement, many temples throughout Matsumoto were demolished or abandoned.

The autumn of 1870 brought the symbolic end of an era at Matsumoto Castle. Entry to the castle grounds had always been a privilege reserved for the social elite, samurai, or guests with special permission. For the first time, regular citizens were also permitted to pass freely through the gates.

In 1871, the domain system was abolished. Matsumoto domain was renamed Matsumoto Prefecture, and Mitsuhisa was relocated to Tokyo. Control of Matsumoto Castle was transferred to the Ministry of War, and an official named Yamagata Aritomo (1838–1922), who would later serve twice as prime minister, was sent to seize the weapons stored in the castle.

The Partial Destruction of Matsumoto Castle

Excavations of the Ōtemon Gate Courtyard

After the second bailey of Matsumoto Castle became the property of the prefectural government, many of its gates, earthen walls, and towers were demolished, and the building materials were reused elsewhere. For example, it is said that lumber from a tower on the wall of the second bailey was used to build a police station in the third bailey, and stones from the Ōtemon Gate were used to build the Sensaibashi Bridge over the Metoba River. It is believed that several gates on the outskirts of Matsumoto originated from the castle grounds, but there is little evidence to support this claim.

Kinoshita Naoe (1869–1937), a social activist and author born in Matsumoto, witnessed the numerous changes to the castle grounds when he was a student at the Kaichi School. He recounted scenes from this time in his novel Hakaba (Graveyard):

“The stone walls of the gates, the large trees on the banks of the moats, everything was disposed of unceremoniously. That old tree on the bank, which they said a mujina had mischievously set on fire, where a three-eyed ōnyūdō demon had supposedly appeared, even it was quickly put to the axe. Anyone who heard the chopping came to a halt and gazed on from across the moat. None of us could stand to think that we were hearing its roots being hacked apart.”

In 2012, excavations were conducted at sites near the Ōtemon Gate courtyard and near a portion of the moat to the east of the gate. An unexpectedly large number of roof tiles were discovered, and it is believed that tiles from the Ōtemon Gate and the surrounding walls were simply dumped into the moat when the structures were destroyed in the early years of the Meiji era (1868–1912).

Meiji Era (1868–1912) to Present Day

Trial Site for the Matsumoto Agricultural Society

In 1880, a group of 50 local residents formed the Matsumoto Agricultural Society. This organization was granted permission to use a section of the castle’s main bailey, which they turned into an agricultural trial site. There, the society experimented with growing new varieties of fruits and vegetables, which were distributed among its members.

According to a memoir written by poet Kubota Utsubo (1877–1967), from around 1891 to 1895, the middle of the main bailey was a vegetable field, the western side near the castle was an apple orchard, and the northern side was a vineyard. In order to raise funds, the society laid out tatami mats in the Moon-Viewing Tower and charged an admission fee to enter the Great Keep.

The trial site was later shut down when the government decided to reallocate the land to Matsumoto Middle School.

Construction of Matsumoto Middle School

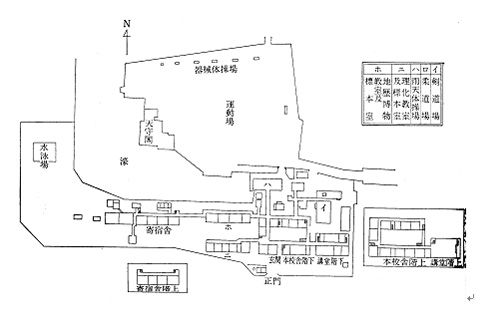

A multicolored woodblock print of Matsumoto Middle School at the time of its opening in the second bailey

Matsumoto Middle School (equivalent to a high school today) was established as part of the Kaichi School on July 10, 1876. To accommodate the growing number of students, in 1885 the middle school broke off to form its own independent institution and moved to the former site of the Kosanji Goten, in the second bailey of Matsumoto Castle. Matsumoto Middle School remained in the second bailey until 1935. The diagram below shows the layout of the school as it was in 1919.

In 1902, the school needed more recreational space, so the main bailey was converted into a sports field for the students.

Layout of Matsumoto Middle School in 1919 (Source: Nagano-ken Matsumoto chūgakkō, Nagano-ken Matsumoto Fukashi kōtōgakkō kyūjūnen-shi 長野県松本中学校 長野県松本深志高等学校 九十年史)

Castle Grounds as a Public Park

Matsumoto Castle was designated a National Historic Site in 1930. Management of the castle grounds was transferred to the Matsumoto City Government, which planned to convert the grounds into a public park. Matsumoto Middle School was moved away from the castle to the Arigasaki neighborhood in 1935. In 1938, the city government established a set of formal guidelines outlining the use of the castle and started drafting specific proposals for a park. World War II began the following year, however, and the project was put on hold.

Work on the public park resumed after the end of the war. In 1948, trees were planted in the second bailey, and other efforts were made to restore the plant life. A small zoo was set up in the southeast corner, near the City Museum, which had been relocated to the second bailey in 1937. A fountain was added to the outer moat. An amusement park for children was also opened in the northwest corner of the third bailey in 1957, and it operated until 1987. In 1968, the City Museum was renovated and reopened as the Japanese Folk Museum (now the Matsumoto City Museum).

Filling in the Moats

With the expansion of the city and the opening of the castle grounds, it became impractical to maintain the three moats that surrounded the castle. The process of filling in the moats began in 1876, with the eastern section of the outer moat and the southern section of the outermost moat. In 1877, the land reclamation efforts began in earnest. A large area around the Ōtemon Gate was filled in, and in 1879, Yohashira Jinja Shrine was erected on the newly reclaimed ground. When the Matsumoto Courthouse was built in the second bailey, an eastern portion of the outer moat was filled in to facilitate foot traffic. The fortified sally ports (umadashi) that had protected the entrances to the third bailey were completely removed by the late 1890s, and even part of the inner moat was filled in around 1905 to make more room for Matsumoto Middle School.

Removal of the moats continued into the Taisho era (1912–1926), when more sections of the outermost moat and the outer moat were reclaimed to expand residential areas. The last portion of the outermost moat was converted into a public swimming pool in the early Showa era (1926–1945).

However, it was eventually acknowledged that the moats were a fundamental part of the castle compound and an important aspect of the city’s history. In 1997, an initiative was launched to restore the southern and western portions of the outer moat.